TRADITIONAL PRACTICES - USOS Y COSTUMBRES

By Barbara

Schaffer

In

this magazine, we have written much about the peoples of the coast:

their customs, music, food and crafts. But we have missed something

of equal interest, something that cannot be photographed, visited,

experienced or purchased, and yet that has attracted the attention

of the outside world. I speak of the unusual autonomy enjoyed by

each of Oaxaca's 570 municipios (counties).

Although

Mexico, with a federal government and 32 states, plus the DF, is replete

with competing mazes of bureaucracies, the municipality is the basic

form of local governance. Our federal and state taxes end up here,

when it comes to community services. The teachers are paid by the

state and follow a national curriculum, but the municipalities build

the schools. Public works, primary health care, water, markets, police

- these are some of the responsibilities of a municipal government.

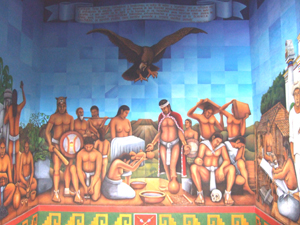

The

roots of the municipal system date back to pre-Hispanic Mexico, but

local government was also an integral part of the colonial regime.

The Constitution of 1917 recognizes the importance of the "Free

Municipality" as a territorial division having certain, fundamental,

administrative responsibilities. Mexico has 2,435 municipalities;

more than 1/5 of them are in the state of Oaxaca.

It

can be argued either way as to whether it's a good thing for Oaxaca

(pop. 3.6 million) to have so many small municipalities in a country

where most are quite large. The entire state of Baja California (pop.

2.8 million) only has five. But one thing is certain, and that is

that Oaxacans are closer to their local governments than are most

other Mexicans.

San Pedro Amuzgos

In

1995 the State of Oaxaca took the radical step of allowing each of

its municipalities to decide on its own form of elections. Prior to

that year, the candidates for municipal president, tax collector,

and various commissioners ran as members of a political party, and

the voting, at least in theory, was by secret ballot. The reality

was that the PRI party controlled the great majority of the local

governments. The new law allowed each municipality to decide if it

wanted to choose its officials according to its own traditional practices

(usos y costumbres) or if it wanted to continue with the political

party system.

History

At

least since the 1960s, indigenous rights groups had been demanding

political autonomy for native communities throughout Mexico. The new

law satisfied many of these demands by giving legal recognition to

already established practices. But it wasn't just to protect indigenous

rights that two successive PRI governors - Heladio Ramírez

López (1986-1992) and Diodoro Carrasco Altamiro (1992-1998)

- pushed the legislation through. Since 1980 the PRI had been losing

deputies in state elections, and supporting direct democracy was seen

as a way of staunching the flow. It was better not to have any official

PRI connection with the municipal governments than to have the PRD

or PAN win another local election.

Most

of the 418 municipalities which chose usos y costumbres had been PRI

strongholds. The 152 which went for keeping the party system tended

to have a history of multiparty elections. Locally, San Pedro Mixtepec

voted for party elections, and Santa María Colotepec opted

for usos y costumbres.

Traditional

Practices

The

basic model (with many possible variations) starts with the selection

of candidates by the municipality's Council of Elders. The Elders,

almost always men, have attained to this office by having, over the

years, donated their time and money to a prescribed number of functions

ranging from serving as constable to sponsoring the yearly feast of

the patron saint. (Not so long ago, the first step on the ladder was

being the town messenger, which included running from village to village.)

Palacio municipal, Jamiltepec

The

Elders present their list to the municipal assembly which then debates

on the merits of the candidates and has the final vote. It is up to

each municipality, to decide, according to its traditions, who is

included in the communal general assembly. In most communities all

adults born in the municipality have the right to participate in the

assembly, but that is far from being the universal experience.

In

some municipalities, only people living in the county seat (cabecera)

can vote, in others non-Catholics are excluded, and 80 of the 418

municipalities (almost 20%) do not allow women to vote in municipal

elections. (In some others women do not participate without their

being a formal prohibition.)

Although

it may shock our liberal, one person-one vote sensibilities, the system

of usos y costumbres is not meant as a step away from democracy but

rather as a recognition of the right of indigenous people to follow

their own traditional political practices. Thus where consensus is

seen as higher virtue than simply getting the most votes, voting is

done by voice, by standing behind a candidate, or by drawing a line

on a black board.

San Pedro Amuzgos

Does

the system work? Not always, judging by the relatively high number

of contested elections that have to be referred to the state for mediation.

But few, if any, of the municipalities which chose usos y costumbres

in 1995 have voted to return to the former system of party politics.

Santa

María Colotepec

As

may be expected, local traditions have changed enormously in recent

years in Colotepec, a municipality of over 13,000 inhabitants, many

living in Puerto Escondido. Here the general assembly includes every

resident with a federal voting card, even naturalized citizens, and

anyone who wants to may run for office. Since around 2000, the assembly

has voted by secret ballot. In this case, usos y costumbres means

that voters must go to the county seat of Colotepec for the meeting

of the general assembly to cast a ballot, and candidates cannot run

under the auspices of a political party.